PROFESSOR GILBERT MORRIS ON THE ART OF AMOS FERGUSON | 8 October 2020

( Amos Ferguson, a Bahamian intuitive artist, according to the National Art Gallery “ Amos Ferguson was born in 1920 in Exuma. He received his primary school education at Roker’s Point School in Exuma. Ferguson came to Nassau in 1937 to learn a trade. He dabbled in various enterprises such as upholstery and furniture finishing. Finally he went into house painting and began painting on cardboard, drinking glasses and whatever he could find after receiving divine instruction. He first sold his works in the Straw Market but soon made his home on Exuma Street (now Amos Ferguson Street) his studio”. He died on 19 October 2009 This piece was contributed by Gilbert Morris and was first published in Wakonte Caribbean—Editor)

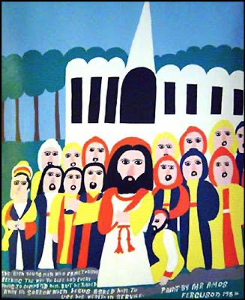

“I paint by faith, not by sight,” said Mr. Amos Ferguson, the late Bahamian artist, now renowned globally. In sentiments consistent with form he said further: “To paint, the Lord gives you a vision, a sight that you go by,” he once told a reporter. “But don’t forget you have to see and check that Bible and don’t forget God. And the more you keep up with your Bible, and get the understanding, the better you paint.”1

Here then is a painter who takes inspiration and directives not from any existential force as a result of the mysteries of. being, but from divinely wrought intuition, as a sight to go by…to get the understanding. This is a theme, not uncommon amongst “intuitionist” artists, whose discussion of their art asserts, ironically, both an uncommon assurance and a submission to a power beyond the artist himself and his audience.

As biographies go, the New York Times re-tells the legend as follows: “Mr. Ferguson, a house painter by trade, did not turn to art until he was in his 40s, when, as he told the story, a nephew came to him and related a dream he had just had. Jesus, the nephew said, came out of the sea with a painting in his hands and said Mr. Ferguson was wasting his talent for painting. Mr. Ferguson heeded the call and, painting with exterior enamel on cardboard, rendered Bible stories or Bahamian scenes in a vibrant Caribbean visual idiom. 2

What is notable here is that the “inspiration” to create art is not Ferguson’s intuitively or directly, but rather his nephew’s. Yet, Ferguson’s oeuvre is flourishing testament to this “surrogate inspiration”, with an attendant resolve to master the gifts his nephew reported were already reposed in him no less than by divine bequest.

Amos Ferguson’s art is characterized by multitudinous dualities, everywhere, the first amongst which are Christian and pagan. He regales us by means of a halo-dramatic palate of colour, organic, measured and unprepossessing, depicting images from biblical stories, Junkanoo and ordinary Bahamian scenery in a naturalistic pastiche. Without wanting to quibble, it would seem that some theological accommodation ought to be required to bring ‘divine inspiration’ into unison with a Godless street festival, (Junkanoo) – which originated for the same or similar reasons the ‘Children of Israel’ demanded graven images from Moses’ brother, Arron.

However, in Ferguson’s work, biblical reference and Junkanoo appear together, emerging ostensibly from a single inspiration; not unlike the admixtures and active, (though incongruent unities) of the profane and the divine in Bahamian life. 3

This co-habitation of the divine, the mundane and the pagan is not new: The Bahamas is a national boundary without a definitive culture, (owing largely to a lack of self-recognising education and the “paradise myth”…akin to the Renaissance in Italy), in which the enigmas of arrival – from native genocides, pirate republics, enslaved migrations, to tethered independence as result of colonial exhaustion – ushered in a turnstile of both socio-cultural and psychological instabilities, which undermined, reshaped and refashioned and displaced into a shifting pantomime, the foundations of belief, knowledge and culture in the Bahamas.

What was clear, then as now, is the confutation of disparate influences, such as we find unacknowledged and so unresolved in Ferguson were vital to the expression of the spirit of the times: As one Renaissance scholar put it: “Not all the painters could take what they would of the diverse gifts of [the age] and ignore those for which they did not care. Sometimes the two influences, Pagan and Christian, meeting together, produce a jarring discord, which will not be silenced”. 4

In sentiment and subject matter, Amos Ferguson – was alike to renaissance artists – in that, neither his biblical imagery, nor his reflections on Bahamian culture are culturally corrective or critical. He does not question the Bible. He does not ask how a people who arrived in the Bahamas by unbiblical means speak so biblically, yet – so often – live anathema to what the Bible confirms, teaches or aimed to enforces in Christian possibility or potentiality. Specifically, the autodidactic painter or the maker of “outsider art” is often characterised as being “precocious”, with all of the forgiveness of innocence that implies. Strikingly, in Anthony Petullo’s Collection of Self-taught artists, “The History of Self-taught & Outsider Art”, self-taught artists are paired with, and their work compared to the mentally ill or insane.